Who really is in charge during surgery? Are the surgeons liable for everyone, including CRNA's? Recently, AANA posted an article dissecting the the "Captain of the Ship" concept, shedding light on who really is "in charge" or liable during an operation. The answer might surprise you.

Ambulatory Surgery & Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

Did you know that approximately 20% of adults may suffer from Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)? And 7% of those exhibit moderate-to-sever OSA. However, up to 80% of patients go undiagnosed and untreated. So why is this important when talking about ambulatory (outpatient) surgery you ask?

Well, OSA is the most common breathing disorder occurring during sleep. It is characterized by partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep despite continuing ventilatory efforts. Patients with OSA are at high risk of peri-procedure complications such as respiratory depression and decreased pharyngeal muscle tone, which may enhance airway obstruction and lead to hypoxia, hypercarbia, arrhythmias and ultimately cardiopulmonary arrest.

When you combine OSA with ambulatory surgery, complications can arise. Most commonly, the use of sedative and anesthetics, muscle relaxants and opioids may worsen or trigger upper air way obstruction. These drugs also decrease the natural response to low oxygen and high carbon dioxide levels in the blood. Finally, the stress of the surgery itself can cause heightened symptoms of OSA, typically occuring several days after surgery.

Since anesthesia and sedation can have a negative impact on patients with OSA, let's discuss the proper way to determine if a patient is suitable for ambulatory surgery.

Preoperative Considerations

- Assess the existence/severity of OSA pre-procedure to ensure that patient selection is appropriate for the type of procedure and anesthesia planned

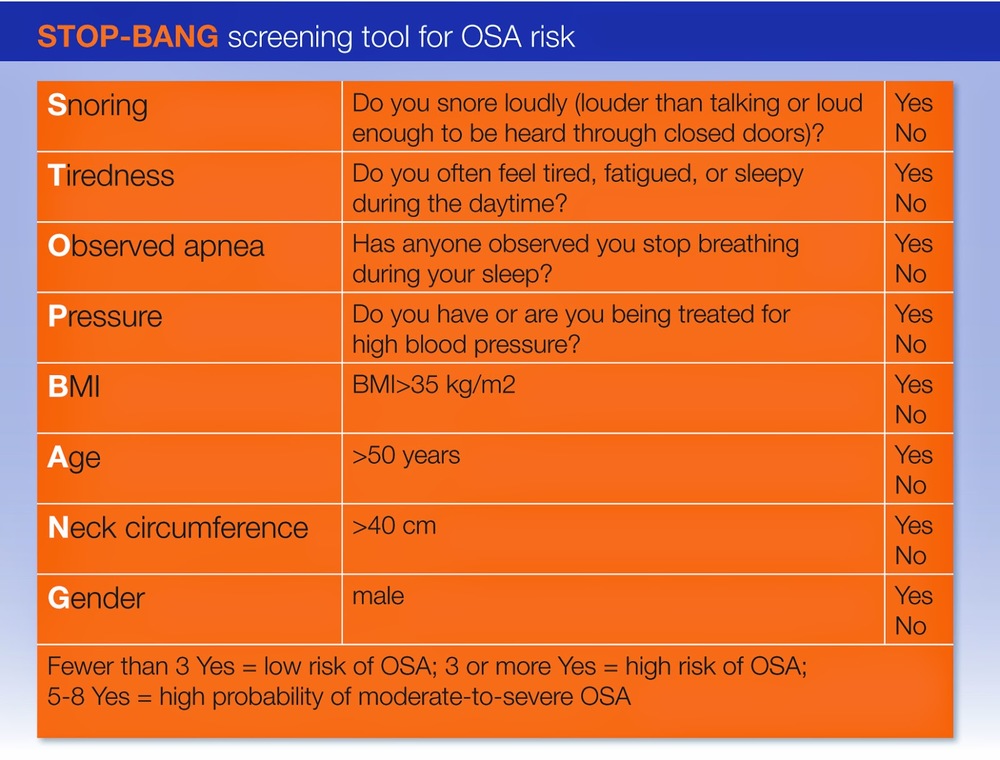

- Follow the STOP-BANG outlined by the Society of Ambulatory Anesthesia (SAMBA).

- Take into consideration the level of invasiveness of the surgery and anesthesia, as well as the potential need for post-procedure opioids.

- Pre-procedure education should encourage use of CPAP machine, sleeping in semi-upright position postoperatively and warning about the dangers or and/or the need to avoid opioids.

Anesthesia

(Use non-opioid analgesic techniques, when possible)

- Local or regional anesthesia should be used whenever possible

- If moderate sedation is required, continuous capnography should be used during the procedure

- If general anesthesia is planned, providers should preferably use a technique that allows early emergence

- If opioids are required, use short-acting ones, when possible

- Consider non-opioid multimodal analgesia approach (local/regional analgesia, non-steriodal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen.)

Recovery

(Facilities should be prepared for respiratory care and have transfer agreements with inpatient facilities.)

- Place patients in a semi-upright position

- Observe patients for oxygen desaturation and/or apneic episodes.

- If oxygen desaturation occurs while on supplemental oxygen therapy of on preoperative CPAP, use non-invasive ventilation.

- Avoid systemic opioids, if possible. If necessary, titrate to the lowest dose that works for long acting opioids (morphine and hydromorphone)

- Patients who are noted to easily obstruct their airway when drowsy should receive extra vigilance.

Postoperative Considerations

(Exercise caution in OSA patients who develop prolonged and frequent sever respiratory events (sedation analgesic mismatch with opioids, desaturation, and apneic episodes) in the postoperative period.

Significant Respiratory Depression

- Appropriate resuscitation should be incited

- Consider transfer to an inpatient facility for additional monitoring

Post Discharge

- Patients who are suspected of having OSA based on clinical criteria should be encouraged to follow up with their primary care physicians to consider a sleep study

- Post-discharge education should include a recommendation to continue use of CPAP while sleeping (day or night) and a warning about the dangers of and the need to avoid opioids.

**{NOTE}**

It is important to state that patients that present for sedation type procedures (cataracts, GI cases) with sleep apnea need to be told that they will be receiving sedation not general anesthesia. They may hear and feel things during the procedure and due to their airway the amount of sedation they receive may be less to assure a safe anesthetic and procedure. Airway assessment and communication between the patient and the anesthesia clinician is imperative to assure patient safety.

This article is an excerpt from the Institute for Quality Improvement's Patient Safety Tool Kit: Ambulatory Surgery and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Download the brochure here.

.

Anesthesia Sedation: The After Affect

As we all know anesthesia comes in varying degrees. It can be conscious sedation, to monitored anesthesia care where the patient gets very little sedation to deep sedation. It can also be general anesthesia or combination of all of those mentioned with a regional technique.

Regardless of the type of anesthesia what we need to remember is this….anesthesia affects everyone differently. The onset of Propofol has made the outpatient anesthesia experience very pleasant for patients. If used as the sole source of anesthesia the patients wake quickly with little to no side-effects and are alert and oriented when they leave.However, when sedation is given by using a combination of benzodiazepines and narcotics; with or without Propofol, patients may respond differently post-procedure.

Before patients can leave a facility they must meet the discharge criteria determined by that facility. Their vitals are stable, they can drink, go to the bathroom and ambulate without problems. They may feel a little groggy but they know what is going on and appear “normal.” The problem is there is really know way of knowing how the patient really feels. They will tell the nurses they feel fine and they probably do but ask them an hour later and they will not remember talking to the nurses.

The medications given in a combination anesthesia will cause amnesia and a lack of inhibition, like an intoxicated type state. The degrees of the state of inhibition may vary but this behavior is something that we as anesthesia clinicians need to be more conscious of. We tell people that they should not drive following sedation or general anesthesia; we tell them they should not make important, life changing decisions. But, do we tell them they should not get on the internet?

In a recent article I found the following incident that occurred:

“Recently, a patient’s husband was upset when his wife returned for a diagnostic test. On further discussion, it was revealed that his concern wasn’t the quality of care, the size of the bill, the amount of the deductible, or the length of the wait, but the fact that his wife had spent a large amount on the Home Shopping Network (“HSN”) during the afternoon following her last procedures and sedation.”

After reading this I realized that we owe it to our patients to ensure that they truly understand the affects that anesthesia may have on them and advise them accordingly. In our high tech world we should stop and consider that people may get on line and shop

or even text people and say things they may not normally say. This could cause devastating consequences that ultimately we as clinicians could be responsible for.

Source: PhySynergy

Exelon Patch May Complicate Use of Neuromuscular Blocking Drugs

Transdermal delivery systems or medicated patches such as the Exelon patch can require alternative anesthesia plans during surgery. Read and excerpt from the Anesthesa Patient Safety Foundation titled,

Rivastigmine (Exelon) Patch May Complicate Use of Nueromuscular Blocking Drugs, to find out how the Exelon patch can affect patients during surgical procedures when mixed with Nueromuscular Blocking Drugs (NBD).

(Photo courtesy of Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation article)